The Pokémon franchise has always liked to use places from the real world as an inspiration for the setting of its main games. Although the first four regions are heavily based on Japanese regions and islands, the more recent games are inspired by western countries. As to this day we count the United-States, France, the United Kingdom and, from the newly released Scarlet and Violet game, the Iberian Peninsula. To be precise, Spain with a flavor of Portugal.

Pokémon games have never aimed to be strictly accurate to a region or a country. Regardless, when playing the game, it is obvious that a lot of research has been made to evoke Spain and Portugal on various levels: language, architecture, landscapes, economy… not to mention gastronomy. In this article I’ll show how a video game can play a pedagogical role in the learning of real world history, through the in-game references of the Iberian Peninsula’s geopolitical history in the Pokémon region of Paldea.

The Iberian Peninsula, like many European regions, has been exposed to many cultural influences throughout its history – through trades, exchange of ideas between scholars, but also through military invasions leading to long-term occupation by the victors. The game, while accurately representing the architecture and art traditionally associated with Spain and Portugal (« traditional » houses, roman and gothic buildings, modern Gaudí architecture, etc.), takes care to show the main different cultures whose importance can be seen today in different parts of the Iberian Peninsula.

I’ve counted three of them: Roman culture, Islamic culture, and Basque culture.

Let’s start with the Roman, the most easily recognizable as such by a large audience.

The Iberian Peninsula was among the first targets of the ever expanding Roman Empire. Not all of it was conquered at the same time, but parts of the Iberian Peninsula were under the Empire’s rule for about six centuries (200 BC-400 AC). It had a major influence on the local population, obviously in the language (both Portuguese and Spanish being Latin languages), but also notably in the architecture. This is visible multiple times in the real-world and the game.

Running around the region, the player encounters at least fourteen Roman or part-Roman ruins, each different from the others and featuring multiple assets among those: pillars, cobblestones, amphoras, arches and broken walls (up to two-storeys).

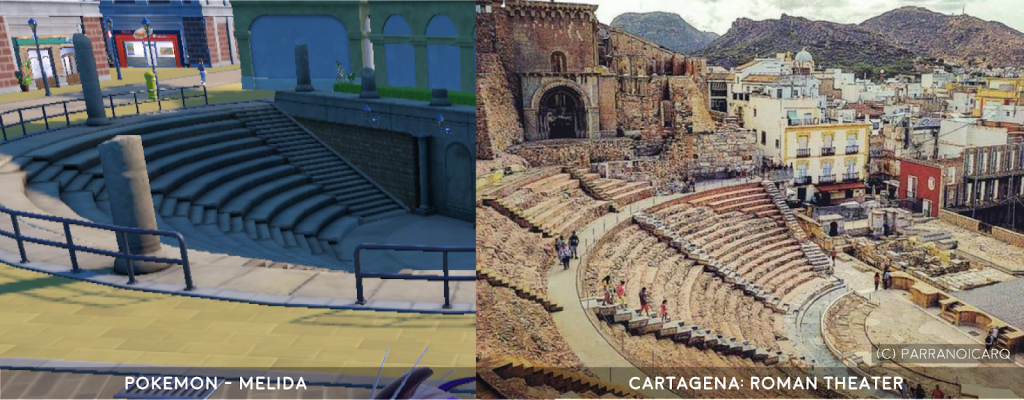

But the most obvious example of Roman architecture is the ancient theater in the city named Medali (A1). As a direct link to history, one of the passersby explains to us that “long ago, the space at the bottom of these stairs was a stage for plays and concerts”. The name of Medali itself is a reference to the Spanish city of Mérida (A2) (the Spanish ‘r’ being similar to an English ‘l’), which houses the most famous Roman theater of Spain, listed as a UNESCO World Heritage site. But the situation of the Pokémon Roman theater, in the center of the modern city, is unlike Mérida and seems to be a mixed reference with other famous Roman theaters like the ones of Malaga (A3) or Cartagena (A4).

The French translation of Medali is a reference to the city of Zamora (A5), which has a Roman past and is geographically located nearby.

That is how the Roman heritage of the Iberian Peninsula is acknowledged in the game. A player from Asia or North America, who might only have a vague idea of what Spain is actually like, could understand through those few pieces of pixel architecture that Spain was part of the Roman Empire at some point in the past.

After the Roman Empire met its end, the Iberic Peninsula was invaded by several Germanic groups. Foreign troops from the north of Africa were hired to fight in order to solve internal quarrels but, finding the Iberian Peninsula to their taste, they decided to conquer it for themselves through the Strait of Gibraltar (separating Europe and Africa). The conquered region, which included the whole of Portugal and the majority of Spain, was called Al-Andalus. In some parts, the reign of the Muslim rulers lasted around 8 centuries (700 AC-1500 AC) before they were pushed back to Africa.

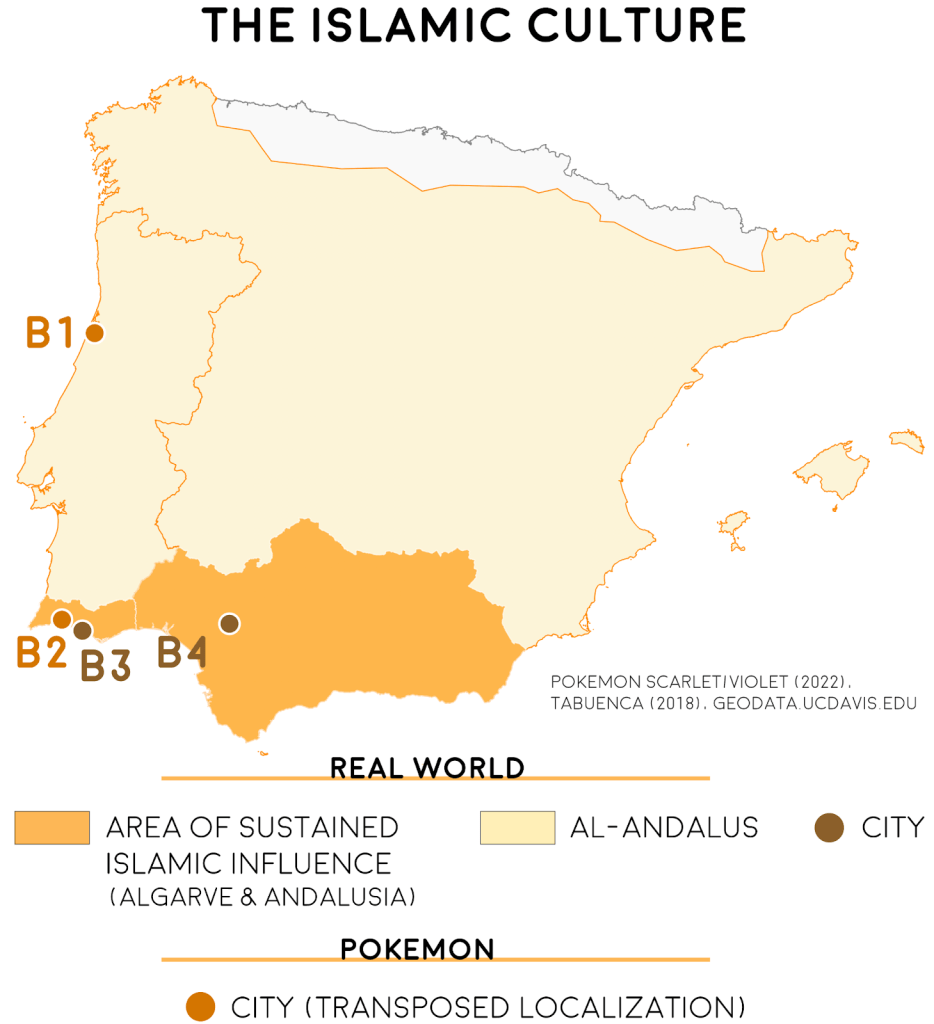

While the Roman heritage is shown mainly in the “Spanish” parts of Paldea, the existence of Islamic culture is shown more clearly in the “Portuguese” parts (the Portugal-inspired cities being Cascarrafa, Porto Marinada and Alfornada). The ceramic artworks in the hall market of Porto Marinada (B1), seen again on the houses of Alfornada (B2), originate from a type of art (azulejo) brought to Portugal and Spain. But the most striking Islamic features are found in the most southern city of the map, Alfornada.

The architecture there is different from the usual European-coded buildings found in the rest of the game. It’s especially visible in the shape of the roofs, very flat with a type of dome that is used in Islamic architecture to lower the air temperature. The tall chimneys rising above the rooftops are found in the southern part of Portugal, with a design inspired by the Islamic culture and its minarets. The square tiles on the side of the walls might be a reference to the traditional “window grids” (mashrabiya) used to cool the interiors.

As for the cultural influence, we are told that Alfornada’s battle court was “originally built as an observatory to view the stars”. Modern astronomy owes a lot to the Islamic world, and we see at the top of the court an armillary sphere, used in astronomy. In Europe, it was created in Ancient Greece before being later picked up. This sphere is featured on the Portuguese flag. We can notably find one in Albufeira (B3), a city located where Alfornada would be in the Iberian Peninsula and who inspired the French version of the name Alfornada, “Alforneira”. The German name is instead inspired by the city of Seville (B4), which was the capital of Al-Andalus for a century.

Islamic flat roofs might be less directly recognizable than ancient Greek/Roman stone pillars, especially in a franchise that has already used the ancient architecture imagery (most recently with the ruins and ancient temples in Pokémon Legends: Arceus). But a lot is done by the gamemakers to help the player make the connection: through the localisation (at the very south of the country), the stereotypical architecture (as, even in cities with flat roofs, you wouldn’t find a dome on every roof), and the music theme (you can hear the OST here).

The situation of the Basque culture is different from the Islamic and the Roman cultures, two people who invaded the Iberian Peninsula, colonized it for a few centuries before they were forced to leave. Basque people have lived in the Pyrenean mountain range for several millennia both on what is now the north of Spain and the south-west of France, and still live there today. They have their own language, and the Basque houses (etxe) are very recognizable by their dark half-timbering (traditionally red, sometimes brown or green). In the Pokémon game, we can see such houses in both Artazon (C1) and Montenevera (C2).

Having Basque houses in those two very different cities is a clever choice. While it makes sense that the traditional “ice” city (Montenevera) is Basque, given their link to the Pyrenees, the Basque country is best known for its green fields and closeness to the sea, as we see near Artazon. The other Basque references in Artazon are very light ; the only possible one is a Skiddo, a goat Pokémon, near the person welcoming us in the city: living in the mountains, as the Basque were traditionally shepherds. The Tagtree Thicket (C3), at the south-east of Montenevara, is a gamified version of an existing Basque painted forest (the painted forest of Oma (C4)).

There is no other noticeable reference to the Basque culture in the original version of the game.

But in the French version the city of Montenevara is called “Frigao”, which is a mix of the French slang word for freezer and the city of Bilbao (C5), the most important city of the Basque country. The Spanish version even makes the city name half-Basque: “Pueblo Hozkailu”, Hozkailua being the Basque word for freezer. The Spanish version is, unsurprisingly, the most detailed version regarding Basque culture: among the three challengers of “Pueblo Hozkailu”’s arena, two of them have traditional Basque names (Mikel and Amaia), and the third one has a way of speaking recalling the Basque language (using k instead of qu, and tx instead of ch).

Pokémon Scarlet and Violet has been acclaimed for its representation of Spanish (and, to a lesser degree, Portuguese) culture. While they obviously deserve praises for their work, what I find even more impressive is the attention to “superfluous” details. The Pokémon games have never claimed to be strictly representative of the truth, which means that they could’ve gotten away with identical stereotypical Spanish and Portuguese houses on the whole map. But research has been made on the geopolitical history of the Iberian Peninsula and the different cultures that influenced it through the ages.

The three cultures presented here aren’t equally known or recognizable, so the pedagogical value of the game varies.

Faced with the Roman theater of Medali and the dozens of ancient pillars and amphoras all over the country, the players can understand that the Iberian Peninsula once had something to do with the Roman Empire. While the Islamic architecture can be harder to recognize (for Western players at least), with the soundtrack of Alfornada surrounding it helping put it in context. In addition to learning about the Islamic presence on the south of the Iberian Peninsula, the player is confronted with the importance of astronomy and ceramics for the Portuguese, on which the Muslims played a large part.

The Basque country is different because it isn’t well-known beyond France and Spain. Seeing Basque houses won’t ring a bell to the average player. But the Spanish-speaking players from every part of Spain (and other Spanish-speaking countries worldwide) can be reminded of the Basque people, of their architecture and, through their translation, their way of speaking.

About the author: Amélie Soubie is a French PhD student in Geography. She’s interested in how games use scientific knowledge to create entertainment content, and especially in world building.

Acknowledgements: The editor acknowledges the assistance and guidance of Dr. Stephannie Mulder and Dr. Glaire Anderson when referring to the architectural classifications.

Map sources:

Gilmart D. (2018), Romanización de Hispania, URL : https://historicodigital.com/romanizacion-de-hispania.html

Leclerc J. (2022), “Brève histoire de l’Espagne hispanique et de ses régions” , in L’aménagement linguistique dans le monde, URL : https://www.axl.cefan.ulaval.ca/europe/espagne_histoire.htm

Tabuenca E. (2018), Invasión musulmana, URL : https://www.unprofesor.com/ciencias-sociales/invasion-musulmana-resumen-facil-para-estudiar-1540.html